To view the origional blog post on the Pro Bono Economics webpage click here.

The question above may seem straightforward, but it has proven surprisingly difficult for organisations working in education to answer. Thanks to support from Porticus Foundation, as part of IntegratED, we have been able to work with the Learning Team at HeadStart, a National Lottery-funded programme aimed at improving young people’s mental health and wellbeing, to shed some new light on this issue.

Permanent exclusion from school is fortunately a relatively rare event, but it has been associated with worse life outcomes. Recent Department for Education (DfE) statistics show that nearly 4,000 pupils were permanently excluded in 2020/21, down from a pre-pandemic level of more than 5,000 in 2019/20. Fortunately, this amounts to just 0.05% of all pupils. However, we know from Edward Timpson’s landmark review of school exclusion that these pupils will disproportionately face worse long-term outcomes. Just 7% of children that are permanently excluded go on to achieve good passes in English and maths GCSEs; they are more likely to go on to be out of education, employment and training in those critical years after the compulsory schooling age and 23% of young offenders with sentences of less than 12 months have been excluded previously. While exclusion is not necessarily the cause of these worse outcomes, it does, at the very least, identify a group of young people that have high levels of need for support.

This has led Timpson and many others to highlight the need for earlier interventions to help schools support those at risk of exclusion, in order to try and improve these young people’s long-term life outcomes. But this naturally leads to the challenge of how we can identify which young people are at risk of exclusion and quantify them.

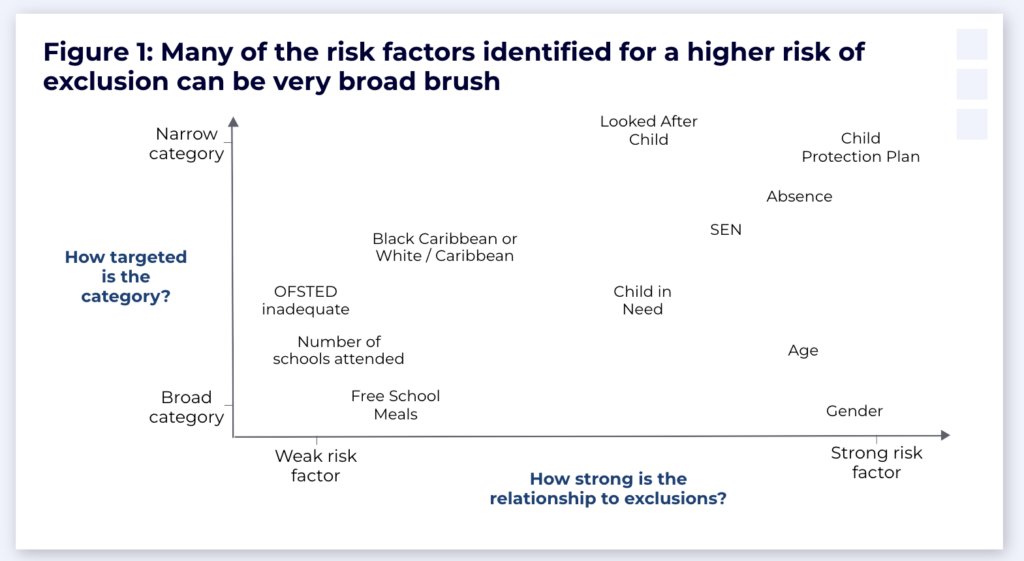

The Timpson Review provided valuable new evidence on this issue. It highlighted that age, absence from school, certain types of special educational needs and being known to social services, were all important risk factors associated with exclusions (eligibility for free school meals, a school’s Ofsted performance, ethnicity and a young person regularly changing schools were all highlighted as being slightly weaker risk factors in comparison). While this analysis will inevitably provide only a partial picture - incorporating solely data available at a large scale in administrative databases, rather than the local knowledge of education professionals – it provides a robust basis for starting to identify key risk factors.

Unfortunately, there are challenges to using these risk factors in practice. In particular, many of the risk factors are very broad brush; applying to a large number of pupils, which makes them ineffective for targeting support.

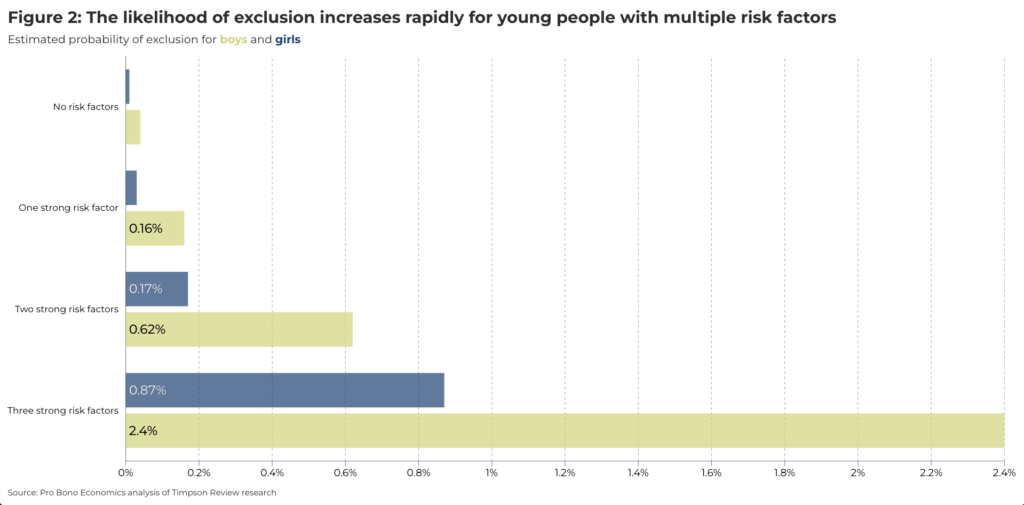

However, the Timpson analysis highlights that the risks “multiply up” - meaning that the likelihood of permanent exclusion for someone with more than one risk factor could be significantly higher than for someone with just one of the risk factors. We can draw on the Timpson analysis to explore this effect. As Figure 2 shows, if a young person is faced with just one risk factor then their risk of exclusion increases, but maybe not by as much as people would expect. However, if a young person faces three risk factors then these risks interact and the likelihood of someone being excluded starts to become far more material.

This then raises the question of whether we can make greater practical use of these risk factors by focusing on a narrower group of young people that have multiple risk factors. However, we cannot immediately work out from the Timpson analysis how common it is for a child to have multiple risk factors.

To try and gain an understanding of this, we have drawn on analysis completed by the HeadStart programme to explore this issue in more detail. Started in 2016, HeadStart was a six-year, £67.4 million National Lottery funded programme set up by The National Lottery Community Fund. It aimed to explore and test new ways to improve the mental health and wellbeing of young people aged 10–16 and prevent serious mental health issues from developing. The six HeadStart partnerships were based in Blackpool, Cornwall, Hull, Kent, Newham, and Wolverhampton. As a test and learn programme, the HeadStart programme ended in July 2022, with many of the approaches having been sustained and embedded locally. The Evidence Based Practice Unit, based at the Anna Freud Centre and University College London (UCL), is leading the final national evaluation that will be completed in mid-2023.

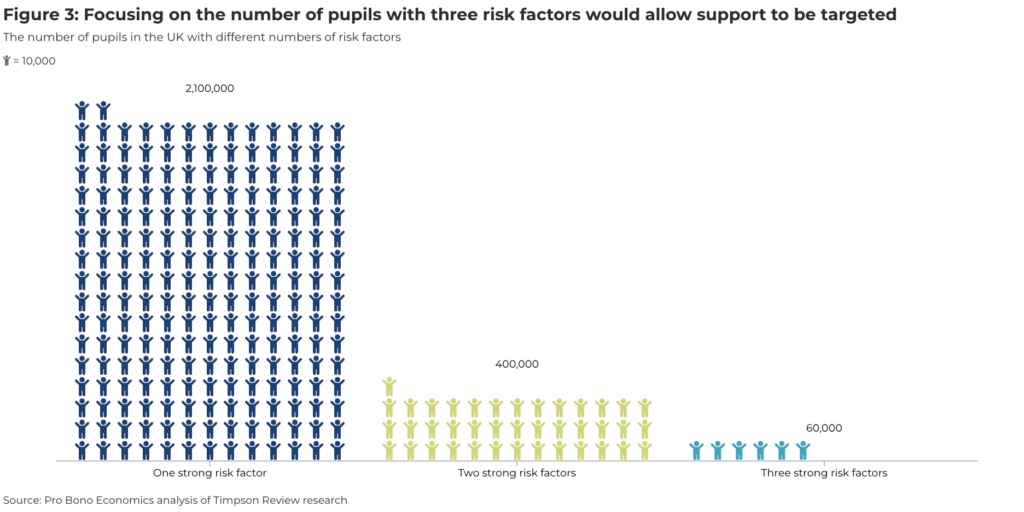

We used the data gathered by HeadStart to explore the proportion of pupils facing multiple risks of exclusion, and what that would imply for the total number of pupils at different levels of risk. If we extrapolate the findings for a single cohort of year 9 students out to a typical school, it suggests that:

- 68% of pupils will have one strong risk factor - this is unsurprising given that some of the strongest risk factors identified by the Timpson review were whether a child was in Year 8, 9, 10 or 11 of school.

- 14% of pupils in a typical secondary school will have two strong risk factors.

- However, just 2% of secondary school children will have three or more strong risk factors.

If this data is representative of the broader picture across the UK, this means that across England the number of pupils with one strong risk factor is likely to be 2.1mn, the number with two risk factors could be around 400,000 and the number with three risk factors is likely to be around 60,000.

This clearly has implications for the level of support that can be provided to these groups of pupils. While providing in-depth support to more than 2mn pupils is not going to be feasible, focusing support on those with three or more risk factors sounds far more realistic – the equivalent of just 16 pupils in the average state-funded secondary school.

So, are we able to answer the original question about the number of young people at risk of permanent school exclusion in the UK? There is not a definitive answer to this – it depends on what we mean by “at risk”. However, based on current evidence, we would suggest that a pragmatic answer could be to focus on those children facing at least three of the strong risk factors identified by the Timpson Review.

Evidently, there is a need for more work in this area. The analysis we have discussed in this blog has been very simplistic, not designed specifically to help with targeting support. For this reason, Pro Bono Economics will be collaborating with education charity FFT to improve the analysis of risk factors - with a particular focus on understanding if there are specific combinations of risk factors that are more important for determining the likelihood of exclusion than others. The hope is that by combining this insight, based on universally-available data, with local education professionals’ knowledge about young people’s social circumstances and emotional wellbeing, it could provide a valuable tool for identifying those with the greatest support needs.