Mental health trailblazers: are they including excluded children?

The link between poor mental health and exclusion from school is well documented – both as cause and effect.

According to the government’s 2017 mental health green paper, Transforming children and young people’s mental health provision, pupils with mental health difficulties are more likely to have their education disrupted due to time off from school or exclusions, compared to children with no mental health issues. Moreover, research suggests exclusion may aggravate, or even precipitate, poor mental health. A study by the University of Exeter found that not only were young people with mental health difficulties more likely to be excluded, but that exclusion led to new-onset mental health conditions, despite adjusting for background factors.

In December 2018 the government announced its mental health trailblazer programme to provide support to young people in schools and in July 2019, it confirmed a further 57 trailblazer areas to be added to the existing 25. The programme, delivered jointly by the DfE and the NHS, sees targeted support delivered in schools through newly established Mental Health Support Teams (MHSTs) operating in the trailblazer areas and across clinical commissioning groups.

MHSTs are made up of four Education Mental Health Practitioners (EMHPs) and supported by NHS Children and Young People’s Mental Health service staff. EMHPs are Band 5 NHS practitioners with one year of clinical training.

Their remit includes the following core functions:

- delivering evidence-based interventions to children and young people with mild to moderate mental health issues;

- supporting the senior mental health lead in each education setting to introduce or develop a whole-school or college approach to mental health and wellbeing; and

- providing a point of contact for liaison with other external mental health services.

With around one in eight children aged 5 to 19 estimated to have at least one mental health problem, improving access to psychological support through co-delivery and co-location with schools is a welcome first step. According to Professor Tamsin Ford, the lead researcher from the Exeter study cited above, access to mental health support is crucial to “prevent exclusions and improve educational and health outcomes later in life.”

Nevertheless, early intervention is just one piece of the puzzle.

By the time a child is excluded and being educated in alternative provision (AP), the level of presenting need tends to be much greater. In addition, the distribution of pupils with social, emotional and mental health (SEMH) needs is not equal across school types. Two thirds of pupils in AP have an identified SEMH need, compared to 13 per cent of children in special schools and just 2 per cent of children in mainstream schools.

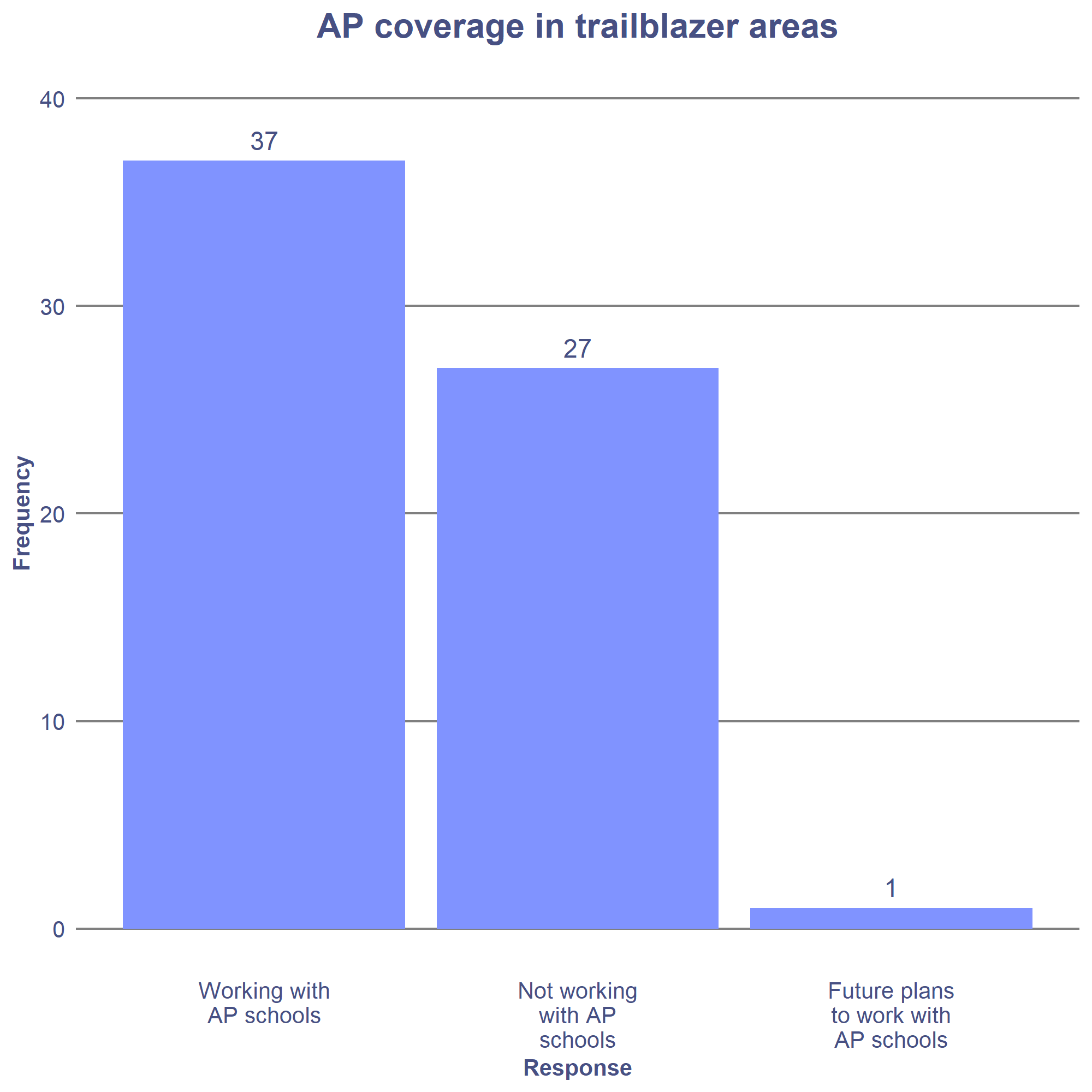

In its response to the 2017 green paper, the government stated its commitment to ensuring that MHSTs “reach those most in need of support” and “are accessible to all, including those not in mainstream education”. In order to understand how far the government has delivered on that promise, the Centre for Social Justice sent freedom of information (FOI) requests to all the trailblazer areas to ascertain the level of coverage and expertise provided to AP schools. In total, we received 65 responses.

We found that just over half (57%) of trailblazer areas are working with AP schools and a further one has plans to. This means that over four in ten areas are not working with excluded children.

More often than not, MHSTs are supporting a single AP school in an area – usually the pupil referral unit. In 11 trailblazer areas, MHSTs are supporting more than one AP school.

In one trailblazer area, the MHST is working with pupils in the AP school only if the pupil is dual registered with a mainstream school.

The AP pupil population differs significantly from the pupil population in mainstream school. This was reflected in many of the trailblazer’s responses. They described their students’ needs and vulnerabilities as “complex”, “multiple” and spanning “severe trauma”, “loss”, “bereavement”, “abuse”, “attachment issues”, “parental mental ill health”, “substance abuse issues”, “unstable family situations” and “extreme/volatile behavioural issues”.

Given the above, it should perhaps be concerning that of the trailblazer areas that are working with AP schools, just 22% have a specific strategy in place to work with pupils in these settings. According to experts from the Anna Freud Centre, EMHPs are insufficiently qualified to deal with the level of need and complexity of the pupil population in AP without significant additional support. Claire Evans, Head of Workforce Development at the Anna Freud Centre, describes the situation as follows “EMHPs are trained to deliver low intensity CBT for low mood and anxiety. This is highly efficacious for less severe problems but will be far short of what would be recommended for the vast majority of children and young people in AP.” This was recognised by a number of trailblazer areas, of which at least one reported having shared this concern with NHS England.

Of the trailblazer areas that do have a specific strategy in place, approaches range from involving senior AP staff in trailblazer strategy meetings, to supporting AP school staff development and wellbeing, through to providing significant senior clinician time. In almost every instance, this targeted approach was described as “needs-led”.

Government-commissioned research into AP highlights the importance of having a clear strategic plan that articulates a shared understanding of the role of AP and sees the provision of AP as a delicately balanced system. The same can also be said for the way that MHSTs interact in their local contexts.

For one trailblazer area, this means complementing the existing CAMHS provision. The PRU already has a service-level agreement in place with CAMHS, which provides a specialist worker three days per week. As a result, the MHST focuses instead on group work and staff training, freeing up senior Band 7 CAMHS clinicians to work directly with pupils.

Similarly, in another area, most of the MHST resource is allocated to supporting staff, discussing individual pupils and signposting to appropriate services in recognition of the fact that the MHST’s services are “not ideal” for their pupils’ needs.

In one trailblazer, a senior clinician from the MHST is offering art therapy to the AP school, with another trialling short-term cognitive behavioural therapy. If it is found to be helpful, the team plans to allocate a practitioner based on assessed need.

In addition to supporting staff and pupils in AP schools, some MHSTs are actively sharing best practice with other schools. For example, one trailblazer area has created four team clusters acting as centres of excellence, one of which is the PRU. The PRU is described as having a key role in “sharing best practice with other AP schools and influencing and encouraging its peers to recognise and welcome early access to mental health support.”

Finally, still other areas have focussed their AP strategy on partnership working. In one trailblazer area, for example, the MHST is supporting the PRU with multi-agency consultations and access to Anna Freud Centre workshops, while another is offering its expertise at local behaviour and attendance meetings.

It is heartening to see innovation and collaboration with AP schools arise from the mental health trailblazers, but there is more to be done. Given the rate of SEMH is 33 times higher in AP schools than mainstream schools, and the needs more acute, we would like to see the following from the government:

- Recognition that AP schools require a higher level of expertise than the EMHPs are able to provide.

- An analysis of need across AP schools to determine the level of expertise and staffing required to best serve those pupil populations.

- Advice for existing trailblazers on how best to serve the AP population.